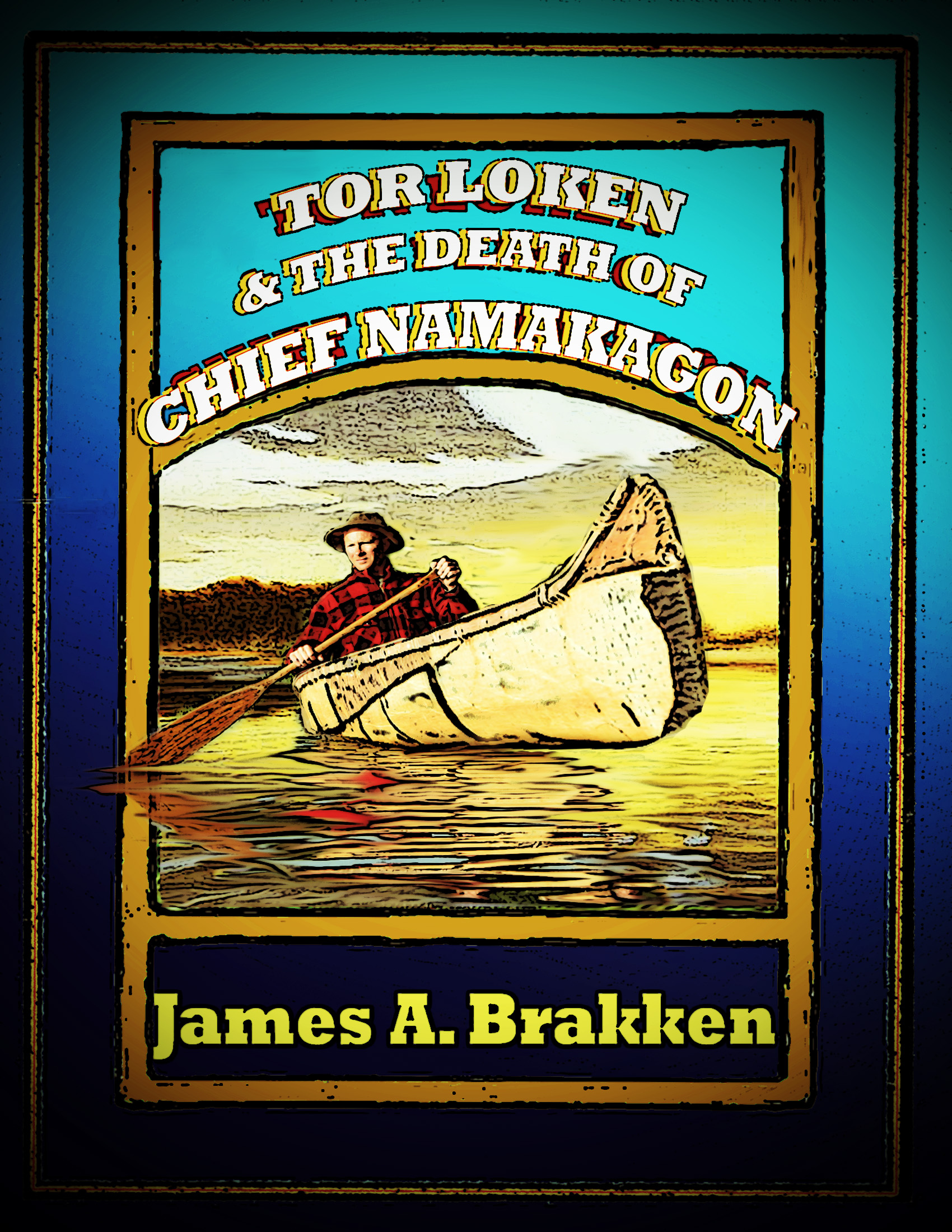

Tor Loken & the Death of Chief Namakagon |

|

$ 17.99 USD |

|

|

|

|

Step into the 1880s, an era of lumber camps, lumberjacks, and lawless wilderness boom towns. Join Tor and Rosie as, with you, they solve the dark mystery surrounding Chief Namakagon’s murder. It’s a fast-paced, fact-based thriller by the award-winning Wisconsin author whose research now unlocks the truth. Book 2 in the Namakagon trilogy, this illustrated, 243-page historical fiction is written for adults although suitable for age twelve and up. It is a thrilling, mystery-adventure you won’t want to put down.

When murder plagues a remote northern Wisconsin lumber town in 1886, a young lumberjack risks his life to trap Chief Namakagon’s killer and safeguard the secret silver mine. A thrilling, fact-based murder mystery.

Button your mackinaw and lace up your boots. You are about to plunge into a fact-based tale of timber, treasure, and treachery in America's 19th century wilderness—a twisting, turning, thrilling north woods mystery based on the suspicious 1886 death of Chief Namakagon.

Following a severe November gale on Lake Superior, Namakagon’s body is discovered near a secluded silver mine. Our hero, nineteen-year-old Tor Loken, is determined to prove his mentor is a victim of murder. Suspicious accidents soon plague his father’s backwoods lumber camp. Tor and his sweetheart, Rosie, risk their lives to protect the tribal treasure against insurmountable odds as they plot to trap the treacherous, shrewd killer.

SampleChapters: 1 & 2:

The Lucerne

November 16, 1886

The dismal cawing of distant crows cursing the end of the harvest could not spoil this perfect Indian summer day. Strolling along Ashland’s waterfront, nineteen-year-old Tor Loken opened his mackinaw coat to soak in the southwest Lake Superior breeze. He passed steamship after steamship, some laden with ore from nearby iron mines, others waiting for cargos of virgin Wisconsin white pine.

High above the steamers stretched the three tall masts of the Lucerne, a well-trimmed schooner stowing aboard the last of her iron ore cargo. Tor admired the handsome vessel with her scroll head and clean lines. Two men stood near the wheelhouse. One, a younger man, sported a fashionable tan suit and bowler hat. The other fellow’s hat had the mark of a ship’s captain. It matched his blue overcoat, adorned with gold braid and bright brass buttons. A thick, black beard hung below the cigar he chewed with the arrogance of a seasoned seafarer.

From high in the mizzenmast rigging came a sharp call. “Ay, land lubber! You come to sail the seven seas with us?”

Tor looked up. “Why, if it isn’t Junior Kavanaugh, lumberjack turned sailor! You look like a gol-dang horsefly caught in a spider’s web way up there in those ropes. Say, you did not have to come all the way to Lake Superior just to climb a tree. Still plenty of ’em left near Pa’s lumber camp.”

“Ya, Tor, but from these here poles I will soon cross ol’ Gitchee Gumi and then see the world, not just some wilderness lumber outfit.” Junior began his descent, shouting, “Billy! Say, Billy, look who come to see us off.”

Billy Kavanaugh and the ship’s captain stepped to the rail. “Well, Tor Loken,” yelled Billy. “Welcome to the shipping trade where the real money sits a-waitin’. Come aboard. Meet George Lloyd, Captain of the Lucerne. I hired the captain and his ship for a run to Cleveland ’fore me and Junior set out for the tropics.”

“What brings you to Ashland?” asked Junior, jumping the last few feet from the rigging. “Your lumberjack pay burnin’ holes in your pockets? If so, there are taverns, poker rooms, and sportin’ gals a-plenty here to relieve you of your money. Take my word!”

“Junior, your pa sent me. He wants you back in camp—back on the job with him and the fellas at the Namakagon Timber Company. He is worried about you workin’ on the ore boats.”

“Worried?” snapped Billy. “Now, ain’t that Pa for you? Why, I have sailed from Boston to Brazil and Nassau to New Orleans time and time again. Not once did Pa ever show the slightest margin of concern for me, his eldest son. Junior, take my advice and just you never mind Pa. Lumberjackin’ is a far sight more perilous than the shipping trade. Many a shanty boy’s lonesome mother and weeping widow can prove me out. Many!”

He turned to Tor. “You listen here, Tor Loken. Junior is goin’ off on a high adventure with his big brother. Our Pa and all you bark eatin’ lumber-grubbers can freeze your gol-dang arses off by day out in them woods, then shiver in your revoltin’ bunkhouse stench by night. Me and Junior don’t give a tinker’s dam. Each one of us will make three times a lumberjack’s winter wage on this Cleveland run alone. We are haulin’ near to thirteen-hundred ton of ore and will soon be trading other goods in the Caribbean. Tor, you tell Pa for us that come summer we will call on him back on the farm in Mazomanie—each wearin’ a diamond stick pin when we do.”

Tor turned to Junior. “Is Billy speakin’ for you, Junior? Is this what you want?”

“You know dang well I do. Much as I like lumber camp life and the good times we had on them cold Saturday nights in town, I gotta do this. You give Pa a fond farewell for me. I am off to see the world, my friend. See the world and make my fortune.”

“All right. I will explain it as best I can.”

“Loken,” said Captain Lloyd, “you tell Mister Kavanaugh his boys are sailin’ on the finest vessel on these Great Lakes. She’s a far sight safer than them smoke-belchin’ steamers. Only thing they are good for is to give a real vessel a tow when her sails go slack—which, by the by, ain’t very often. You tell him the schooner Lucerne and this here captain will keep his boys safe, sound, and secure.”

“I will, Captain. He will appreciate hearing your words.”

“We have us a so’west wind and intend to ship out within the hour, a full day ahead of schedule. Join me and my crew for a quick bite ’fore we cast off?”

“I surely would like to, Captain, but I’m meetin’ my girl at the depot and know better than to keep her waitin’.”

“Rosie?” said Junior, “Rosie is in town? You and your flame gonna kick up your heels some?”

“No, no heels gettin’ kicked up. Ashland is growin’ leaps and bounds, what with all the ships, trains, mines, and lumber camps. There’s talk of startin’ a college here. Rosie wants to study English.”

“Fancy that. Rosie Ringstadt—a highbrow college girl!”

Billy snickered. “What in the blazes for? Gol-dang waste of time, I’d say. It is shameful to fritter your life away, nose stuck in a book. Tell her to take to the road. Travel’s your best schoolin’ by far. I plan to see the whole dang world and get rich along the way.”

“Captain,” said Tor, “it has been a pleasure. I hope the wind stays at your back, sir.”

“Young man, our paths will again cross. I feel it in my bones. Till then, farewell, Tor Loken.”

<>O<>

An hour later, Tor and Rosie walked arm in arm from the railroad yard to the waterfront to see their friends depart. The Lucerne, bound for Lake Erie, soon left Chequamegon Bay in full sail. After watching the schooner round the point, the couple turned toward Ashland’s busy downtown for a meeting with the school headmaster. As they walked, they felt the warm southwest breeze turn southeast. Stepping onto the street after the meeting, they noticed another change.

“Smells like rain,” said Rosie as they boarded the southbound train.

“With fifty men in camp and a hundred more a-comin’, what I long for is a gol-dang good snowstorm.”

“Wishing is folly, Tor. Winter shall come when winter comes—no sooner, no later. Patience reveals change and change offers opportunities to grow.”

“Sakes alive, Rosie, you are startin’ to sound like ol’ Chief Namakagon.” They settled into a seat in the first passenger car.

“Frankly, Tor, I prefer this warm weather. I so envy Billy and Junior, off on a sailing adventure that will take him to the sunny tropics. What I would give if we could be on the Lucerne with them. They are so, so fortunate.”

“Fortunate? Fortune is yours to find, wherever you make your camp. The chief told me that.” He put his arm around her. “Rosie, this passenger car isn’t much like a camp and I know we are not sailing off on an adventure, but right now I would say there’s nobody more fortunate than this north woods shanty boy.”

“Why, Tor Loken! You are such a sweet talker. I hope your other flames do not hear the same.”

“Other flames? Pa keeps me tied so close to camp I never meet any other girls. ’Sides, Rosie, why would I want to? You are the only one for me. You know that, right?”

Rosie smiled. Two whistle blasts pierced the air.

“Well, Rosie? Rosie?”

The Omaha rolled south toward the Namakagon River Valley in hazy, Indian summer sunshine with a murder of crows soaring high above.

<>O<>

As the Lucerne sailed up the west shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula, the wind suddenly died. Captain Lloyd stepped from the wheelhouse, the chewed stub of a cigar between his teeth. He studied the slackened sails, then stared eastward.

“I am not favorin’ this weather, Mister Jeffreys. Such a sudden calm on a warm November midday has the Devil’s mark. Tell the men to rig for a blow.”

“Naw, Captain,” replied the first mate, “she’s a fine afternoon. The wind will pick up. We will be puttin’ in at Sault Ste. Marie in no time.”

“Mark my words, Robert. Something is a-brewin’ in them skies. See to it we are battened down and tell Mister Kavanaugh I need to see him post haste.”

“William Kavanaugh?”

“He signed the contract, Mister Jeffreys.”

By the time Billy and the first mate returned, a southeasterly wind again filled the sails.

“See there, Captain?” said Jeffreys, “We again got us a good breeze. She will be clear sailin’ once beyond Copper Harbor.”

“Aye, but this wind is bound to turn again—bound to change. I can feel it in my bones, Robert, and I don’t take to it none. No sir, Lake Superior is notorious for her November gales. Mister Kavanaugh, I am droppin’ anchor at Ontonagon until we see what is in store with this here weather.”

“Drop anchor?” said Billy. “See here, Captain, I see no reason to delay. I engaged your services to deliver ore to Cleveland, not to bask in the sunshine. Winter is comin’. I say we push on.”

“And I, Mister Kavanaugh, am Captain of the Lucerne. I am responsible for her well-being and the safety of her crew. I will be damned if your desire for profit shall dictate otherwise!”

“One hour then. If the weather favors it, we sail. Will you accept that, Captain?”

“All right, Kavanaugh. An hour it is.”

Sails struck, the Lucerne lay moored in waters off Ontonagon, Michigan. Again the wind turned, now southwest.

“Captain,” said Jeffreys, “I still think she’s a fine day for a sail. Once we round the point, we’ll make good time crossin’ the lake.”

The captain bristled. “Sixty minutes was my agreement, Mister Jeffreys. That’s how long we wait. Now, fetch me a bottle from that case of brandy in my cabin, Robert.”

One hour later the Lucerne weighed anchor and set out in full, billowed sail. Thirty miles beyond Copper Harbor, the eastern horizon grew black with clouds. The wind suddenly shifted, coming straight out of the northeast.

“All hands, Mister Jeffreys,” shouted the captain. “Five degrees starboard. We are in for a squall.” He took a pull from his bottle, jammed the cork in tightly, and stuffed it into his coat pocket. “Shoulda trusted my gol-dang bones.

Within minutes, snow-laden, gale-force winds drove twelve-foot waves over the decks. Ice began to build, clutching to the rigging and sails, coating every surface.

“No use, men,” shouted Captain Lloyd. “There’s no makin’ headway against this tempest.” He tipped up the half-empty bottle. “Mister Jeffreys, I am puttin’ about to find us some lee waters.”

“Aye, Captain.”

As the Lucerne came about, a large wave crashed over the bow. A half-dozen ropes snapped as the mainsail collapsed, tearing as it fell onto the deck.

“Jeffreys,” screamed the captain, “we have no choice now. We must run ahead of her.”

“Aye, Captain,” came a faint reply as Robert Jeffreys made his way through wind, snow, and ice-cold waves blasting over the stern.

“Set what remains of that mainsail, Robert. Satan will have us if we cannot keep up. I am makin’ for the Apostles. We are bound to find lee water there.”

“The Apostles? Sir? It’ll be dark before we …”

“Do not question me, Mister Jeffreys.”

“Aye, Sir. Apostles it is.”

As evening set in, the schooner Lucerne, ropes and sails heavy with ice, sped across Chequamegon Bay. Captain Lloyd strained to see the La Pointe light off the starboard bow. With darkness falling, the wild snow squall turned into a full-blown, fearsome nor'easter. George Lloyd realized if he saw the beacon at all, it would be too late to save his ship and crew from wrecking on the rocky, frozen mainland. Around midnight, a nearly empty brandy bottle in his coat pocket and both hands locked on the ship’s wheel, he gave the order.

“Mister Jeffreys, call the crew topside, the Kavanaugh brothers, as well.”

Seconds later, the sailors heard his command. “Men, I will not further risk the Lucerne. We are puttin’ about, bow into the wind so we can weather this here typhoon. Mister Jeffreys, on my call you sailors drop the bow anchor, then strike the foresails quick as a whip-snap. It’s the mainsails what is next, Robert. Then sharply drop the aft anchor and be quick about it. I mean for every soul aboard to again feel earth under his feet. I will be damned if ol’ Gitchee Gumi will take the Lucerne without a fight.”

“Aye, Sir,” came the mate’s reply. Eight men soon braced themselves against the driving wind, snow, and spray, awaiting the call from George Lloyd.

Grinning defiantly, the captain spun the ship’s wheel. The Lucerne turned windward, leaning far to port, groaning from the strain of wind versus rudder. Completing the turn, she briskly straightened up, proudly facing into the nor'easter and bucking waves now twenty feet between valley and crest.

“Now, Mister Jeffreys. Now!”

Water crashing over the bow masked the loud rattle of the chain. The anchor struck bottom, skidding across the sand, barely slowing the Lucerne and her 1,256 tons of iron ore cargo. As ordered, the crew struck the foresails. The mainsails came next.

With words muted by howling wind, the Captain bellowed, “Drop the aft anchor, Mister Jeffreys.”

“Aye, Sir,” replied the mate over the roar of the storm.

The second anchor splashed into the dark water. With foresails and mainsails furled, the crew, holding tight to the icy rail, worked their way down the slick deck toward the mizzenmast. As they neared this third mast, the bow anchor wedged between rocks thirty feet below, lowering the foredeck. The mizzenmast, sails straining against wind, could not withstand the force. It snapped between crosstrees and crashed down, smashing the port rail before splashing into the lake off the stern, taking with it two men. Only Junior and the first mate heard their cries above the roar of the storm.

“Man overboard!” screamed Jeffreys. “Man overboard, Captain!”

“Nothin’ to be done for ’em, Mister Jeffreys. Satan has us in his grip. Pray they do not drown or freeze ’fore washin’ ashore.”

“Billy! Billy!” screamed Junior. “Captain, one of those men is my brother! You gotta do somethin’!”

“I ain’t riskin’ it,” Lloyd shouted over the storm. “’Sides, no way to find them in the black of night—not in this hurricane-typhoon. You get below, Kavanaugh.”

“Damn you to Hades if you do not find them, George Lloyd!” screamed Junior. “Give me your oath you will find them. Your word, Captain!”

“I will do all I can, Kavanaugh. I will search until I find ’em if it takes an eternity! I swear my soul will not rest until I again have my full crew. Now get below ’fore I have to fish for you, too.”

The Lucerne pitched and rolled wildly in the dark. Making his way below, Junior heard a growling groan and sharp thud as the bow anchor chain broke. Feeling her pitch, tilt, and turn with the wind, he raced back to the wheelhouse. Captain Lloyd lay on the deck, thrown there by the wild spin of the ship’s wheel.

The vessel leaned far to port, nearly capsizing as she twisted in the storm. A gigantic wave broke on her deck, blasting the ice-laden hatch covers up and over the side and taking most of the port rail into the lake. Water rushed into the hatches. The aft anchor dragged over more rocks and, with a deep, heart-stopping snap, broke free.

Now a wind-driven leaf in the storm, the Lucerne rolled far to port, then to starboard in the icy, storm-driven waves. Still turning in the wind, ice fell from the masts, spars, and rigging, crashing onto the deck and crew below. They held to the rail, some throwing lines around their waists, lashing themselves to the boat.

“We have but one chance,” screamed Captain Lloyd, clutching the wheel. “Pray to God she runs onto some spit of sand and is not broken up on the Bayfield rocks.”

George Lloyd strained to regain control of the wheel and rudder. When he did, he reached into his pocket for his final sip of brandy. Pulling the cork with his teeth, he spit it away and finished the bottle.

“Captain, a light!” shouted Junior. “There! Look! A light!”

“God in Heaven!” screamed Jeffreys. “Kavanaugh’s right, Captain. It’s the La Pointe light! Long Island’s off the port bow. We can still make the lee shore off Madeline. Take her to starboard, Captain! Hard to starboard, now! Hard to starboard!”

But the first mate’s words came too late. The Lucerne bottomed out on the shoal off Long Island. Plowing through sand and rock twenty feet below, her hull tore open wide, spilling her iron ore cargo onto the lakebed. Lighter now, the bow thrust out of the black lake, then crashed down, taking on more water. The lower deck flooded. Next, the wheelhouse.

“She’s going down,” screamed the captain. “Every man for himself. Take your chances in the lake or take to the rigging, your choice. I will find you, fellas. May God be with you.”

Captain George Lloyd held fast to the wheel of his beloved Lucerne as four sailors climbed high into the rigging to avoid drowning in the icy, black waters. Two others gambled on the lake, hoping to reach shore. Descending, the schooner’s hull lodged in the sandy lakebed with a stiff jolt. The Lucerne’s bare mainmast and foremast protruded well above the waves while the wind in her rigging howled and howled—a thousand hungry wolves at the heels of their prey.

The snow stopped before dawn, but not the wind, now from the northwest. A bright sun and frigid, blue sky hung over the shipwreck. One mile north, the keeper of the La Pointe light scanned the horizon with his glass, discovering two masts stretching skyward from waters near Long Island.

Risking his life, he rowed out to find three ice-encrusted bodies hanging from the rigging but no sign of the other sailors. In a mere breath of time, the schooner Lucerne lay wrecked, lost to Gitchee Gumi, ill-famed for her Devil-sent November gales.

Unaware that, twenty miles south, the Ojibwe elder known as Chief Namakagon lay bleeding in the deep snow along the Marengo Trail, the lightkeeper returned to Madeline Island. Stroke by stroke, he heard only the rhythmic slapping of waves against his hull and the distant, dismal cawing of crows cursing the coming of winter.

<>O<>O<>O<>

Chapter 2

The News

November 17, 1886

Word of the Lucerne disaster quickly reached every telegraph operator in every depot across the nation. Fifty miles south of the wreck, Oscar Felsman, Stationmaster at Cable, a busy lumber industry boomtown, chose to personally deliver the news to his friends at the Namakagon Timber Company. His horse and cutter fought through twelve miles of deep snowdrifts blanketing the rutted tote road. Oscar reached the lumber camp late that afternoon.

“Olaf,” he shouted, throwing open the big lodge door.

“Olaf is in the barn,” replied Sourdough, setting a pot of coffee on the table. “Ingman and Tor, too. What brings a stationmaster this far from civilization? You didn’t come all this way to pinch me for a few nickels over a pinochle deck, did you?”

“I am here with most dreadful news, Sourdough. News about that ore boat, the Lucerne. The one John Kavanaugh’s boys were on.”

“What of it?”

“It went down in yesterday’s storm.”

“Down? Down where? What in blazes you gettin’ at?”

“It sunk. It got caught up in that blizzard yesterday. Wrecked. Went down just off Long Island—near La Pointe.”

“My God! But …”

“Sourdough, somebody must tell John Kavanaugh. Both of his boys were on the Lucerne. Both boys lost in one night. Can you fathom that? Oh, the poor, poor man.”

“Both boys drowned, Oscar? Both?”

“Word has it that three of the crew froze to death after tryin’ to escape drownin’ by climbing up into the ship’s rigging. One more, the first mate, washed up off Bayfield. The others have not yet turned up. I suppose they are at the bottom of Lake Superior.”

“Then the Kavanaugh boys could be alive?”

“In that storm? That wind we had through the night? What chance would they have, Sourdough?”

“Oh, dear, dear Junior. My dear Junior Kavanaugh. May God save your sweet soul.” Sourdough turned away, eyes wet, staring at the floor. “Oscar, you stay here. Pour yourself a cup. I will get the boss. It’s Olaf’s job to tell John Kavanaugh about his boys. Oh, that poor, poor man. First his wife, now both boys. Poor John. Here, have a chair, Oscar. I will fetch the Lokens. Oh, my God, my God.”

The camp cook left the lodge for the barn, suppressing a desire to scream out in rage and grief. Junior Kavanaugh, his good-hearted, adventurous, young friend was gone. He’d left to seek his fortune. Now it seemed he would never return.

Sourdough stepped through the side door of the barn. “Olaf, Ingman, Tor, I need … Someone needs to speak with you—someone in the lodge.”

“We will be there in a few minutes, Sourdough,” said Ingman.

“You do not understand,” replied the cook. “This cannot wait. Oscar is here. You must come right now.” Sourdough turned, leaving the barn before his friends could witness the depth of his grief.

The three Lokens crossed the lumber camp yard to the lodge and company office.

Olaf entered first, his son, Tor, and Tor’s uncle behind. “Oscar, it is good to see you. What brings you here? Sourdough said you had some news.”

“Sad news, I’m afraid. The ship Junior and his brother were on was wrecked in the storm last night. Off Madeline Island. They are both missing. All the crew, every last soul is thought to be drowned or froze to death. I am so sorry to bring you this horrible news.”

Tor laughed. “You are victim of a cruel joke, my friend. Or a terrible blunder. Rosie and I watched the Lucerne sail northeast out of port yesterday noon. Last we saw her sails, she was well east of the Apostles. By now Junior and Billy are probably kicking up their heels in Ohio and spending their newfound wealth. Oscar, somehow, some way, you, sir, have been duped.”

“No, Tor,” Oscar replied, “the wreck they found is the Lucerne all right. I suffer to tell you this, knowing you and Junior were such close pals. You see, the storm must have blown her back across Lake Superior. The keeper of the La Pointe lighthouse spotted her at first light. He rowed out, hoping to rescue the crew. Found no survivors. The sheriff will probably have a report out by now, but, Tor, from what I saw come across the wire, well, we will ne’er see Junior nor Billy Kavanaugh again. I am so, so sorry.” He turned to Tor’s father. “Olaf, their pa—he must be told.”

“Yes,” said Olaf. “I need to tell John right away. He will want to go look for his boys, I am sure. Ingman, you and I will go with him.”

“I am going, too, Pa,” said Tor. “Junior is my best friend. I have to find him and find Billy, too. Surely they are all right.”

“Son, this is bound to be an unpleasant journey. Your uncle and I will go with John and a few of the men.”

“Pa, I have to help find Junior. I know he is out there somewhere. If I know Junior, he’s wanderin’ around in some woods, a-whistlin’ and a-wishin’ for someone to shout him a hello.”

“No, Son. Better you stay here. Mind the camp till we get back.”

“Pa, for Pete’s sake! This is Junior! My best friend! I have to ...”

“Tor!” snapped Olaf. “You are stayin’ here. That is the end of it!”

Without a word, Tor turned to leave. Crossing the room, he stopped suddenly when, through the windows overlooking the yard, he saw a woman approaching. Two dogs pulled her sled, plowing through the deep snow. “Look. It’s Diindiisi,” he said. “Alone.”

“Chief Namakagon’s woman?” asked Oscar. “Louise Renshaw?”

Tor rushed out the door. Seconds later he helped the exhausted woman into the room.

“Louise! Welcome. What brings you?” said Olaf.

“Mikwam-migwan,” she struggled to say as she collapsed in a chair. “He is lost. Gone.”

“Chief Namakagon? Lost?” said Ingman, “I hardly think so. Old Ice Feathers has lived in these woods for fifty years. ’Tain’t likely the chief would lose his way. An eagle might find itself lost before old Chief Namakagon, old Ice Feathers.”

“No, Ingman Loken. You do not understand me. He was lost yesterday. Lost from the living. Lost from this place—this world.”

“Lost in the storm?” asked Tor.

“No, Tor. He is gone. He is dead.”

“What?”

“Dead. Gone. That’s what they told me.”

“Who told you?”

“The stationmaster at Marengo. I stayed there during the storm. I waited for Mikwam-migwan. He never came. I worried for him. I sang for him. He never came. Then the stationmaster told me Namakagon is dead. He is no more.”

“No! You’re wrong. Namakagon cannot be dead.” shouted Tor.

“I am not wrong. They took him. Took my old man far away. Away from his home. They said he would rest in the Ashland cemetery. Mikwam-migwan’s spirit will never rest so far from his home. It is wrong. Wrong! His spirit is too strong. He will wander. I know this.”

“Are you sure he is gone?” asked Olaf. “Did you see … his body?”

“I watched them put Mikwam-migwan on the train. They would not let me come close. They would not listen. They do not know what trouble they cause. His spirit will never rest. Too far. Too, too far. He will wander for all time.”

Tor couldn’t speak. He turned to his father and uncle for consolation—any relief—escape from all this news. Their faces confessed bewilderment, as they struggled to absorb Diindiisi’s words—grave words about their dear friend.

“Who … who found him?” asked Ingman.

“Derkson,” she replied. “From Ashland. A lawman. He said he found Mikwam-migwan on the trail near our camp. I warned my old man. I said do not go in the storm. He would not listen. Too stubborn. I warned him. Now he is dead. Dead and too far from home.”

“That must be Frank Derkson,” said Tor. “One of the men Chief said had been followin’ him—tryin’ to locate his silver mine. Captain Morgan told me Derkson is crooked as they come.”

“Yes. Frank Derkson,” said Diindiisi, “He is the one who told me my man is gone.”

Tor took her hand. “Diindiisi, does Sheriff Rothwell know about this? He needs to find out what happened.”

“He knows. Derkson said the sheriff has too much work because of the storm. Others died, too. Some were sailors. Derkson told me the sheriff had no time for old Indians. Old, dead Indians.”

“How did Namakagon die?” asked Ingman.

“Derkson said he found him on the trail. Dead. No more.”

“He did not tell you how the chief died? What caused it?”

“No. Maybe Mikwam-migwan could not go farther in the storm. He was old. Maybe he laid down for his last sleep.”

“No.” said Tor. “Not Chief Namakagon. Not old Ice Feathers. Something is wrong—very wrong.” He turned to Olaf. “Pa, I have to go. I know you want me here but I have to find out what happened, how he died, and why he died.” 4681

Olaf looked at Ingman, then at Tor. “All right, but Blackie Jackson is going with you. Hitch a pair of Clydesdales to the big cutter. Take the east trail over to the Wisconsin Central Railway track. Flag down the northbound train. Ingman and I will go with John Kavanaugh up to Bayfield. Sourdough will have to mind the camp. Son, you watch yourself. Let Blackie do the talkin’. Listen, Tor, do not let your hot head overcome your sense of reason. If you learn anything out of the ordinary, go straight to the sheriff with it.

“Louise, you are welcome to stay here as our guest. Long as you please. Tor, Blackie, you best get goin’ while you still have some daylight. Good luck, Son.”

“Same to you, Pa. Find Junior. I know he is out there someplace. Waitin’ for us, most likely. Freezin’ his skinny arse off and wonderin’ what is takin’ us so gol-dang long. I just plain know it, Pa.”

<>O<>

Blackie Jackson and Tor Loken stepped off the train well after dark. They crossed Ashland’s business district to Front Street, checking in at the grand Chequamegon Hotel.

“Where might we find the sheriff, friend?” Blackie asked the clerk.

“Sheriff Rothwell? Oh, he is likely making his rounds ’bout now. Friday night, you know. He keeps an eye on things uptown. Between the sailors, the miners, and the lumberjacks, he has his hands plumb full. He is still tryin’ to deal with the storm, too. Yep, his hands are full, all right.”

“Where might we find the graveyard?” asked Tor, feeling a jab from Blackie’s elbow.

“Cemetery? First you want the sheriff, now the cemetery. You got some news for our local paper? I write for the Weekly Press, now and again. You got some news for me?”

“No, no news,” said Blackie, “just need to see the sheriff.”

“The graveyard is south and east a ways. Other side of the Wisconsin Central roundhouse. Who you lookin’ for, anyway?”

“A friend who they say died in the storm yesterday,” said Tor.

“One of the sailors?”

“A man found down near the Marengo Trail.”

“Oh, the old Indian? The one with the silver mine? Chief Namakagon?”

“There ain’t no silver mine,” said Blackie, “only rumors spread by that newspaper you work for.”

“Sounds like you know all about him.” said Tor.

“All I know is what Frank Derkson told the bartender at the Royale Hotel Saloon.” said the clerk, rubbing his chin. “Said he found the old boy out in the woods southeast of the Marengo Station. Froze stiff. Frank said the old boy most likely drank too much fire water, fell asleep and froze.”

“You mind your tongue,” snapped Tor. “Chief Namakagon would not die that way, no, sir. Who, besides Derkson, might know about this?”

“Whoa, now,” said the clerk. “Take it easy, there. All I know is what I heard across the Royale Hotel bar. You best be asking them questions of yours to the sheriff or to Frank Derkson in person. You will likely find the two of them together. Frank is both a deputy and a brother-in-law to Sheriff Rothwell.”

“I thought Derkson was a miner,” said Blackie.

“Frank? Naw. He filed a couple of claims that never panned out, but Frank Derkson is no miner. More like a mine speculator. Not many folks around these parts that ain’t mine speculators nowadays, I s’pose. Few of them ever do much with their claims, though, besides letting them go back to the government.”

“You said Sheriff Rothwell might be makin’ his rounds right now. Is there a place where we might find him?” asked Tor.

“Were it me, I would try to find a spot near the door at the Royale. Frank and the Sheriff both have interests in some of the women who work there, if y’know what I mean. They stop in from time to time to make sure their girls are keepin’ busy. Seein’ as how it’s Friday, you can be sure them girls will be busy tonight.”

“Interests?” said Tor.

“I will explain it to you, Tor,” said Blackie. “Time we get ourselves down to the Royale.”

“Thanks for your help, friend,” Tor said, laying two coins on the counter. “Here is ten cents for a bucket of beer and another dime to keep all this under your hat.”

“Yes sir! You bet I will. Thank you, sir!”

A quarter hour later, Tor and Blackie leaned against the bar at the Hotel Royale Saloon. Outside, wagons, sleighs, and cutters lined the hitching rails up and down the street. The stores all glowed from oil lamps within. Larger lamps illuminated each intersection. The Second Street boardwalks were crowded with a mix of lumberjacks looking for winter work, sailors hoping for a last run before the shipping season ended, and miners celebrating payday. The noise from those at the bar and poker tables was masked by loud piano music. It filled the room as three women danced on the small stage.

“Barkeeper,” shouted Blackie, “two beers.”

“Blackie, what in blazes are we going to say to the sheriff?”

“I suppose we better let him do the talkin’ till we find where he stands on all this. Let me handle it.”

Two beers later, Sheriff Wendell Rothwell entered the hotel barroom, stomped snow from his boots, hung his bearskin hat and wool coat on a hall tree, and walked straight to Tor and Blackie.

“You boys lookin’ for me?”

“So much for the hotel clerk keepin’ somethin’ under his hat,” said Tor.

“News travels fast in small towns,” replied Rothwell. “Now, what is it you fellas want?”

“We are close friends of the Indian found along the Marengo Trail,” said Tor. “We came to claim his remains for burial near his home. You understand, right, Sheriff?”

“He has already been buried, boy. Seen to by yours truly.”

Tor stood. “You already … Why? I mean, why so soon, Sheriff? What about his wife? His friends? His people?”

“Well, we thought it best to do this right now—before he putrefied on us, you know.”

“In this weather?” said Blackie. “Well, no matter. We are here to take him to his final home. The ol’ boy will have to get dug up.”

“Boys, you don’t want to go wakin’ up the dead. Let him rest.”

“My boss, Olaf Loken, sent us here,” said Blackie. “Chief Namakagon’s wife is waitin’ for us at the camp. We mean to take the ol’ boy back with us, Sheriff, and we would appreciate your cooperation.”

“I will need an order for exhumation before we even consider it. It will take a judge to sign it and the courthouse ain’t open till Monday. Boys, my best advice is to just leave the poor old soul lay where he is. The city will provide a nice marker—stone, not wood—name carved in as well. I will see to it myself.”

“You will see to it?” said Tor. “Sheriff, there is a small island on a lake south of here where he lived for many decades. That land already bears his name. All we want is to take him there so his wife and friends can return him to his home according to Ojibwe ways. Surely, you can understand. Please, Sheriff, help us put our good friend, Chief Namakagon, to rest at his rightful home. It’s only right.”

“Not possible, boy.”

“Sheriff,” said Blackie, “where can we see the death certificate.”

“Ain’t none.”

“Doctor’s report?” said Tor. “Someone must have looked him over, right?”

“Listen, boys, there ain’t no certificates, reports, or nothin’ else to look at. He was just another old, Indian found dead back in the woods. If not for my deputy, why he woulda just laid out there in the snow till the wolves ate him. Then what would you have? Not one gol-dang thing. Boys, I done him and the county a favor by plantin’ his body in our graveyard. I will see to it he gets a marker, like I said. He’s better off. You will be, too, when you stop troublin’ me about this. You hear?”

Blackie stared down on the sheriff. “Where can we find Frank Derkson?”

“Frank? What you want him for?”

“Heard he found the body. We’d like to ask him a question or two.”

“Frank is outa town. ’Sides, you have any questions for Frank, you ask ’em to me. Now, take my advice and let this whole thing be. Leave the poor old Indian rest in peace and avoid yourselves any trouble. I will tell you what, boys. I got a couple of ladies workin’ for me here. How ’bout I call ’em over here along with a couple buckets ’a beer to boot and we call it all fair and square. Whaddaya say?”

“Sheriff,” shouted Tor over the piano, “did Deputy Frank Derkson kill Chief Namakagon in an attempt to find the hidden silver mine? Are you coverin’ up for your brother-in-law—your sister’s husband? Is that what you are doing?”

The piano player stopped, turning their way. The room fell silent.

“Sonny, you will hush your damn voice or I will have you in my jailhouse for disturbin’ the peace. Now you listen here and listen good. That old redskin is dead. Dead, buried, and soon to be forgotten like every other old Indian that I planted up there. Natural causes, each and every one of ’em. Namakagon froze to death, sonny. Got drunk and froze, see? Froze stiff in the blizzard. In weather like this, it could happen to anyone.”

Rothwell stepped closer to Tor and spoke quietly. “Sonny, I’m going to do you and your oversized friend, here, a big favor. If you two are on the next train south, my deputy will not have to cart your carcasses up to our Potter’s Field to plant two more dead drunks found froze along some backwoods trail. You get me, boy? Get out of my city. Get out of my city right now, the both of youse!”

The sheriff strolled back to the door, pulled on his hat and coat, and left the hotel.

“Blackie, what in blazes did I just hear? Why, he as much as confessed his part in the death of Chief Namakagon, didn’t he?”

“Tor, we best skedaddle ’fore he changes his mind. Elsewise, we might find ourselves caught in a real bear trap. Drink up your beer. We need to get ourselves down to the rail yard so we can catch that southbound.”

“Maybe he was lying, Blackie. Maybe, with all the problems caused by the storm, they have not yet buried the chief. Maybe he just said he did so we would let this all go. We cannot give up. We have to go look, Blackie. We owe it to the chief. To his wife. To his people.”

“Much as I want to, Tor, I cannot help you. Not this time. I don’t expect you to understand. I just plain cannot. I had some trouble with the law in years long passed. They would put me away for good if I run up against them now. You will have to take my word on this.”

“Blackie, with or without you, I am going to the cemetery. You catch the next southbound, take the sleigh up to the Marengo Station. Wait for me there. I will be along soon.”

“Your pa would hand me my walkin’ papers if he knew I was leavin’ this to you alone.”

“This is my choice. I owe it to the chief. Go, Blackie. Meet me in Marengo.”

“Much as I would like to, I cannot stop you, Tor. God help you if you run into Rothwell or that deputy of his. I hope you find what you are lookin’ for.”

<>O<>O<>O<>

Chapter 3

Potter’s Field

November 17, 1886

A cemetery is no place to be on a dark November night—especially this night. Still, Tor Loken had to know two things about his friend, Chief Namakagon. Had the chief been buried as Sheriff Rothwell said? And, was the cause of death merely a case of an old man freezing out in the woods? In spite of the sheriff’s threat, his warning to leave the city, Tor felt bound to investigate and now stood in the dark at the entrance to Ashland’s potter’s field, the final resting place for paupers, unknown deceased, indigents, criminals, but rarely Indians.

The streetlights along Front Street, though a mile away, gave a soft glow to the outskirts of town. In that dim light, Tor followed tracks in the snow. They entered the cemetery gate. One track led to three freshly dug, but empty graves. Tor followed the other to a far corner of the graveyard. There, next to a half-dug grave, sat a single, pine coffin. Tor looked back toward the gate to confirm he was alone. He struck a match. The coffin was unmarked. He pulled his knife from its sheath and, one by one, pried up each nail until he could lift the cover.

Tor struck another match. There, in this icy coffin, lay his friend, his mentor, Ogimaa Mikwam-migwan.

----And from the middle pages ----

Here, the sheriff and his deputy are in the Royale bar in Ashland ...

"Just because you wed my sister, don’t think you can take advantage of me and my office. Yes, we are kin. Be that as it may, Frank, I cannot have my deputy runnin’ off to Hayward doin’ odd jobs, some of which you and I both know ain’t in accordance with the law.”

“But ….”

“No, Frank. You tell that high roller who hired you that if he wants someone to help him out, he better look someplace else. There’s plenty of men between jobs this time of year. He will find someone.”

“But Wen, the money is good—real good. Too good to be true. Let me cut you in. ’Tween us two, we can get this all cleaned up in a few weeks, end up with a fine roll of bills in our pocket.”

“I want no part of it, Frank. Whatever it is you are doin’, I know it is beyond the law. I cannot stop you from goin’ out on a limb here, Frank. Just keep it out of Ashland and don’t get found out, hear? And Frank, whatever comes of this, you be gol-dang sure my name don’t come up. Kin or no kin, I swear, if you cause me to lose my badge, I will personally see to it you are hauled in, convicted, and sent away.”

“But, Wendell, I …”

“Listen, Frank, and listen good. I want nothin’ to do with whatever you are involved in. Like I said, you are on your own. Keep me out of it. That’s as far as I can go. You hear me, Frank?”

Derkson stared into his brother-in-law’s eyes, saying nothing.

“You hear me, Frank?”

A tall man wearing a brown tweed suit and a matching derby hat entered the Royale. He spoke to the bartender who pointed to the two lawmen. Sheriff Rothwell studied the tall man now strolling toward him.

“The barkeeper says one of you is the sheriff.”

“That would be me,” replied Rothwell. “And who are …”

“Then you must be Deputy Frank Derkson.”

“Might be. Who are you?”

“Morrison. Captain Earl Morrison. Pinkerton Detective Agency. Chicago office.” His stare remained on the deputy as Rothwell spoke.

“Pinkerton? What in tarnation are the Pinkertons doing in Ash…”

“What do you want with me?” Derkson snapped.

“What makes you think I want anything, Deputy?”

“Well, you …”

The sheriff stood. “Let me handle this, Frank.” He turned, putting his hand on Morrison’s shoulder, turning him. “What is the nature of your business, Detective?”

“Captain.”

“What?”

“Captain Morrison—not Detective Morrison,” he replied, staring at Derkson again.

The deputy stood. “I ain’t done nothin’ wrong.”

Morrison smiled. “I don’t seem to recall saying you did, Deputy.”

“Then, why are you …”

The sheriff interrupted. “Dang it, Frank. Shut your fool mouth. I said I would handle this.”

Morrison stared into Derkson’s eyes, but spoke to both lawmen. “You fellas seem rather nervous. You always act like this? Or, perhaps you only get edgy when a fellow peacekeeper shows up in your town.”

“What do you want, Morrison?” snapped the sheriff. “Spit it out. You’re wastin’ my time.”

“I am looking into some complaints from friends of mine. The Lokens. You know ’em?”

“Heard of ’em. Cannot say I know ’em.”

“You know ’em, right, Deputy?”

“Me? Why would you say that?”

“Seems as though all the folks in the Namekagon River Valley know about you. I hear your name come up right often down there.”

Sheriff Rothwell stared at his deputy now. “And tell me, Morrison, what are these folks sayin’?”

“Captain Morrison, Sheriff.”

Derkson blurted out, “Nobody down there got no right to say nothin’ ’bout me. I ain’t done a thing.”

“Sheriff,” said Morrison, “your deputy sure seems nervous. Bein’ a fellow lawman and all, you and I can easily spot when some fella is sittin’ on a pile of guilt. Deputy, why not just come out and tell us what the trouble is—what you have been up to. Make it easier all around.”

Derkson shook with rage. “No gol-damn Chicago dandy claimin’ to be a lawman has a right to come in here and accuse me …”

“I don’t recollect accusing you of anything, Deputy. Sure sounds like you have some heavy burdens built up inside, though. Best thing you can do is to share ’em, you know. Get ’em off your chest.”

Derkson pulled a revolver from his vest pocket, yelling, “I ain’t gonna stand for no more of this!” As the words left his mouth, Morrison’s hand came up, pulling the pistol from the deputy’s grip and smashing it into his jaw, sending him across the barroom floor, over a chair and into the wall. He jumped to his feet and dove toward Morrison who stepped aside. Derkson landed face first on the bar. As the Pinkerton man ejected six cartridges from the deputy’s pistol, the sheriff lifted his deputy by the collar.

“Enough, Frank. I need you to get over to the office right now. Sweep it out. Check on them two drunk sailors. You hear me?”

“Dammit, Wendell, you ain’t gonna let this …”

“Get out, Frank! Not another word.”

Derkson picked up his change from the bar and stomped from the room. “I ain’t done nothin’. Nothin’, you hear? Morrison, you tell Ingman and Olaf Loken and them other shanty boys down there to stop spreadin’ lies or they’ll suffer for it.” He slammed the barroom door.

Morrison said nothing, offering the unloaded pistol to the sheriff who snatched it from his hand.

“By God, Morrison, I’ve a mind to throw you in jail for disturbin’ the peace. If you had any evidence against my deputy you wouldn’t have done all that chin-waggin’. Instead, he would be in handcuffs and you and him would be on the southbound. Am I right, Morrison?”

The detective said nothing.

“Yes. That’s what I figured. You were hopin’ to trip Frank up. Well, it didn’t work. Now, take my advice. You get your arse out of my city—not tomorrow, not tonight, right now. Next train leaves at the top of the hour. You best be on it. Morrison, I will take no responsibility for what happens if you fail to heed my words. You hear me?”

“Oh, I will be on the southbound, all right, but not because of your warning. I don’t pay much mind to empty threats from penny-ante coppers. I have some advice, Sheriff. You put some distance between yourself and that inept deputy of yours. It is clear he’s involved in something crooked—involved in matters that could send the both of you off to prison. If you’re not already neck-deep, you need to take steps to protect yourself. And, if you are involved, rest assured I will have you in shackles as well as that ham-headed, loose-tongued, brother-in-law of yours. Understand?”

Rothwell said nothing.

“Yes, I believe you do.”

At a loss for words, Wendell Rothwell watched as the Pinkerton man strolled to the front door.

Gathering his nerve, the sheriff shouted, “Be on that train, Morrison.”

The detective opened the door replying, “It’s Captain Morrison. Good day.”

<>O<>O<>O<>

---- And Junior's brother, Billy Kavanaugh, shows how clever a flimflam man he is in this middle chapter. Billy has a stack of bogus mining claims he hopes to sell in the hotel bar across the street and ----

(BTW, this is based on old Ashland Press accounts that Chief Nam traded silver to the druggist, Henry Weed.)

Chapter 20

Doctor Henry White

July 1886

The heavy glass door of Doctor White’s Second Street Apothecary swung closed behind Billy Kavanaugh. The large front windows shook when it slammed.

Before him, Billy saw a narrow aisle flanked floor to ceiling by jam-packed wooden shelves. Both right and left, the shelves sagged under the weight of hundreds of tin canisters, identical if not for hand-written paper labels. Among these tins stood almost as many bottles, some brown, some green, some clear, each capped with cork or glass stoppers. The room had a peculiar odor of pungent herbs combined with noxious chemicals, concoctions created by the good chemist, Henry White.

“Doc?” Billy called.

No reply.

“Doctor Henry White? Are you there?”

Billy stepped to the counter, finding a small, brass bell. He shook it vigorously. “Doctor White!” he called again.

The faint sound of footsteps ascending a wooden stairway came from far in the back. Down the dimly lit aisle, Doctor Henry White emerged from the darkness.

“Doctor White, is that you?”

“Well, of course it is! Who in tarnation did you think would show up when you called my name?”

A short, fat man wearing a white apron and collarless shirt waddled to the front of the store. Standing in sunlight streaming through the large store windows, he slapped his apron. A cloud of powdery dust rose to envelop him.

“What is it you need, young fellow? Be quick, now, I must return to my mixing table. I feel I may be on to a cure for gout. Or perhaps baldness. I do not yet know.”

“Doc, I have been sent here by a Mister Vaughn. He said you would ...”

“Vaughn? Samuel Vaughn?”

“Yes. Sam told me …”

“Then you are not here for medicine, I take it?”

“No sir. No, I am here for ...”

“Vaughn! Why, if that old snapping turtle sent you here to try to get me to sell my share of his mine, let me tell you, young man, it’s a fool’s errand you are on. Furthermore, both you and he are wasting your breath … and my time. Good day.” He turned.

“No, sir. Not that. You see ...”

“Then what is it? Speak up. Can you not see I am engaged in important work here?”

“Yes, well, I apologize for interrupting ...”

“Interrupting? Of course you are interrupting. And I greatly resent those who interrupt. Now, for Pete’s sake, what is it you want?”

“Mister Vaughn said you might ...”

“It is a significant social ill, you know.”

“Sir?”

“Interrupting.”

“Oh. Um … yes. I suppose it ...”

“A sign of very poor upbringing.”

“Yes.”

“We see a lot of it nowadays. Interrupting, I mean.”

“I suppose we do, sir. But back to my reason for coming ...”

“Never used to be that way when I was young. People showed more respect for each other. Why, back then I would not dream of ...”

“Interrupting. Yes, I know, Doctor White.”

“Hmm? Well, as I was about to say before … ”

“Y’know, Doc, I have been from Brazil to Boston and I can tell you the problem is spreading like bacon grease on a hot griddle.”

“You have been from Brazil to …?”

“Wherever you go nowadays, people are interrupting. America, Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, even Peru.”

“Peru? Argentina? Really? You have traveled to ...”

“I have. And you can take it from me, Doc, they all interrupt. I cannot make heads nor tails of it. But, the reason I am here is not about that or your medicines and potions. No, you see, Mister Vaughn said you might have a couple of samples of high grade silver ore I could take on my travels—to show to the natives down there. I would like to purchase a sample. You have any silver for me, Doc?”

“Silver? Yes. Yes, as a matter of fact, I do. Came from the old hermit, Namakagon. Marengo country, I suspect. Or maybe near Pratt. He would not say. Tight-lipped, that Namakagon is.” Henry White reached under the counter. “He traded it for medicine—not for him, mind you. For his people. Very high grade. He brought it in just last week. Shows what is out there if a fellow is willing to look for it, no?”

Billy inspected the fist-sized samples. “How much for this one, Doc?”

“I have no plan to sell ...”

“What is it worth, Doc? Six, seven dollars?”

“Well, I should say so! At least that much. Why, it ...”

“Eight? Nine dollars, Doc?”

“Nine-fifty would be a fair ...”

“Fine. Here is a sawbuck, Doc.”

“I will get your change ...”

“No, Doc. You keep it.”

“But, that’s half-a-dollar too much. Certainly you want ...”

“No, no, Doctor White. To me it’s a bargain at ten dollars.”

“Well, all right, but …”

“And, Doc, please do accept my sincere apologies.

“Accept your apologies? Apologies for ...”

“Interrupting, Doc. It’s a significant social ill, you know. Good day.”

The windows shook as, silver in hand, Billy Kavanaugh left through the heavy front door of Doctor Henry White’s Second Street Apothecary.

<>O<>

The three-and-a-half-pound chunk of high-grade silver ore lay on the counter of the assay office.

“Mister Kavanaugh, based on this sample, I would say your mine is capable of a net yield of somewhere ’twixt ninety-five and one hundred dollars per ton. It’s a rare find, sir.

“Exactly what I had hoped to hear, my good man.”

“I can provide a more accurate assessment, but you will need to bring in a somewhat larger sample.”

“Oh, no, that shan’t be necessary at this time. If you will be kind enough to give me a written estimate of that yield you just quoted, it will do for my present needs.”

“Consider it done, sir. That’ll be seventy-five cents. Anything else?”

“Yes. I wonder if I could ask a small favor. I have taken a room across the street at the Royale. I see by the sign on your door that you close at six o’clock. If you would be so kind as to bring both my estimate and my ore sample to me there after work, I will sweeten that amount by two dollars and buy you a whiskey to boot.”

“Two dollars, sir?”

“Not enough?”

“Oh, no sir. Two dollars will do fine.”

“Very well. Six o’clock then.”

<>O<>

The Hotel Royale barroom was crowded well before six. Billy found a place to lean near the end of the bar and ordered two shots of Old Crow. The assay agent walked in, spotted Billy, and placed the assay estimate face-up on the bar with the ore sample on top. The bartender and several men at the bar watched Billy as he moved the silver and read the paper.

“Holy Mother of God in Heaven!” shouted Billy, turning to the assayer. “Mister, you sure this is right?”

Everyone turned.

“Well, um, yes. Yes, that’s what we ...”

“Hoorah! Hoorah! I struck it big! My silver claim has finally come in!” yelled Billy into the room. “Bartender!, Here is a double sawbuck. Drinks are on me—me and my silver claim!”

“Three cheers for this young fella,” shouted a well-dressed man wearing a tall top hat. “Hip hip ...”

“Hoorah!”

“Hip hip ...”

“Hoorah!”

“Hip hip ...”

“Hoorah!”

Chapter 22

Engine No. 99

September 1886

A silent rain fell across the pinery through the chilly September night, soaking the lush, boreal forest. The showers stopped after dawn. Patches of blue sky strained for a stronghold as bright beams of sunlight stabbed through the hazy mist.

Tor climbed into the cab of the Namakagon Timber Company’s locomotive number ninety-nine, purchased from the Omaha Railroad Company. He joined Klaus Kerwetter, a teamster turned engineer. Behind the huge, black engine, the tender car was stacked high with hardwood slabs for fuel. Seventeen cars came next, each loaded with white pine timber headed south to sawmills in Chippewa Falls, Eau Claire, and Menomonie. Farthest down the track, the last car carried the latest Namakagon Timber Company investment, a steam loader. Permanently mounted on a flatcar, it could lift the heaviest of pine logs on and off the railcars.

“Klaus, have you seen my Uncle Ingman? I swear he said he wanted me to join him here today.”

“Ingman? Oh, ya, ya. He vent on ahead. He told me to tell ya ’bout the change of plans. Said he vould be a-vaitin’ for ya at da Pratt depot.”

“Pratt? Did he say why?”

“Ingman said he vould go to Mason to look at some sawmill dere. Might buy it, he thought.”

“Sawmill. Yep, sounds like Uncle Ingman, all right.” Tor leaned out the cab window, looking down the line of cars. “Who’s the brakeman?”

“Vashburn, I tink is his name. Ya, Nick Vashburn.”

“You figure this Washburn knows the ropes—knows this is a steep downhill grade?”

“Oh, ya, ya, Tor. Vashburn knows plenty when it comes to railroadin’.”

“How about you, Klaus? You got the hang of this hand-me-down iron horse?”

“Tor, you know vell as me I prefer usin’ my oxen. But, gol-dang it, times are surely changin’. Changin’ awful fast. Gust and Ingman both give me a pretty good schoolin’ on the ninety-nine. Yunior, too. Say, that vippersnapper, Junior, sure knows dese dang machines, ya? I swear dat little fella stands good two foot taller ven runnin’ a steam enyun.”

“So, Klaus, you are sure you know how to handle this locomotive?”

“Oh, ya. Sure as shootin’.”

“You actually made a run with her?”

“Made a run? Tor, I already I made me tree runs down ta Pratt mit no problem. Ninety-nine’s boiler I got stoked up real good. Old girl’s got her steam up and she’s a- rarin’ ta roll. You comin’ along, den?”

“You bet. Throttle up when ready, Mister Engineer.”

Klaus pulled down on the brim of his hat and gave two blasts on the engine’s whistle. Far behind, the brakeman leaned out, waving a flag. “All clear, den.” He tapped a gauge, checking the boiler pressure one final time, opened a valve, released the air brake and firmly pulled back the hand-throttle. “Here ve go.”

With a rush of steam, the huge piston, responding to the pressure, pushed the massive connecting rod rearward, turning both enormous drive wheels. They shrieked and spun on the wet rail for a moment before gaining traction, then slowly lugged the engine forward. As they did, each successive coupling in the line of cars pounded the next with a loud slam as the massive weight went into motion. Engine straining, the train crept forward, slowly gained speed, then soon rumbled northwest toward the mainline junction some twelve miles ahead on the steep downhill grade.

Pressure in the boiler soon brought the train up to a comfortable speed. Klaus backed off on the throttle, now letting gravity take over. As they approached the bend at Trappers Lake, Klaus opened the brake valve slightly. The train slowed before entering the bend.

Now, with the bend behind and a hill ahead, two whistle blasts cut through the air. The engineer spun the brake valve, closing it. Then he opened wide the throttle to make the ridge. Smoke billowing from the stack, the locomotive grunted her way up the grade, made the curve at the hilltop and started her final, three-mile descent to the station. Approaching the steepest section of track, the engineer cut back on the throttle and again reached for the brake valve.

“Tor, give me a hand mit dis valve, ya? Seems she’s stickin’ a bit. Must be gummed up, some.”

They tried to turn the brake valve’s brass wheel as the train slowly but steadily gained speed. Grabbing a wrench, Klaus loosened, then tightened the locknut behind the valve’s wheel.

“Looks to be froze up tight, Klaus. Grab that hammer. I’ll turn the wheel while you give her a whack.”

Tor strained to open the brake valve as the engineer slammed it with the three-pound hammer.

“Again, Klaus!”

Klaus grunted a loud grunt as he brought the hammer down on the brass valve. The wheel snapped, yet the valve remained closed.

“Lord Mother Mary help us!” Klause screamed. “Ve lost our gol-dang airbrakes!”

“Set the hand brake before she gets up too much speed.”

Klaus pulled back on the lever. They heard the locomotive’s steel wheels squeal against the cold rails. Smoke billowed out from behind each wheel, but the heavily laden lumber train continued to gain speed. Klaus reached up, gave three short whistles, then three long followed by three more short. He then gave a long succession of short blasts, alerting anyone down the line to clear the track.

“Klaus, the hand brakes on each car have to be set. I’m gonna work my way back. Hope Washburn is already workin’ his way forward.”

“Tor, you vatch out now, she might not hold da track. Be ready to yump!”

“Jump? No, we have to stop this train.”

Trees flashed by as Tor climbed across the top of the wood-filled tender. When he saw, far behind, smoke billowing from under the flatcar,